An Essay Toward a History of the Black Man in the Great War

Foreword

The mayor of Domfront stood in the village inn, high on the hill that hovers green in the blue sky of Normandy; and he sang as we sang: “Allons, enfants de la patrie!” God! How we sang! How the low, grey-clouded room rang with the strong voice of the little Frenchman in the corner, swinging his arms in deep emotion; with the vibrant voices of a score of black American officers who sat round about. Their hearts were swelling—torn in sunder. Never have I seen black folk—and I have seen many—so bitter and disillusioned at the seemingly bottomless depths of American color hatred—so uplifted at the vision of real democracy dawning on them in France.

The mayor apologized gravely: if he had known of my coming, he would have received me formally at the Hotel de Ville—me whom most of my fellow-countrymen receive at naught but back doors, save with apology. But how could I explain in Domfront, that reborn feudal town of ancient memories? I could not—I did not. But I sang the Marseillaise—“Le jour de gloire est arrivéd!”

Arrived to the world and to ever widening circles of men—but not yet to us. Up yonder hill, transported bodily from America, sits “Jim-Crow”—in a hotel for white officers only; in a Massachusetts Colonel who frankly hates “niggers” and segregates them at every opportunity; in the General from Georgia who openly and officially stigmatizes his black officers as no gentlemen by ordering them never to speak to French women in public or receive the spontaneously offered social recognition. All this ancient and American race hatred and insult in a purling sea of French sympathy and kindliness, of human uplift and giant endeavor, amid the mightiest crusade humanity ever saw for Justice!

Contre nous de la tyrannie,

L’etendard sanglant est levé.

This, then, is a first attempt at the story of the Hell which war in the fateful years of 1914–1919 meant to Black Folk, and particularly to American Negroes. It is only an attempt, full of the mistakes which nearness to the scene and many necessarily missing facts, such as only time can supply, combine to foil in part. And yet, written now in the heat of strong memories and in the place of skulls, it contains truth which cold delay can never alter or bring back. Later, in the light of official reports and supplementary information and· with a corps of co-workers, consisting of officers and soldiers and scholars, I shall revise and expand this story into a volume for popular reading; and still later, with the passing of years, I hope to lay before historians and sociologists the documents and statistics upon which my final views are based.

Senegalése and Others

To everyone war is, and, thank God, must be, disillusion. This war has disillusioned millions of fighting white men—disillusioned them with its frank truth of dirt, disease, cold, wet and discomfort; murder, maiming and hatred. But the disillusion of Negro American troops was more than this, or rather it was this and more—the flat, frank realization that however high the ideals of America or however noble her tasks, her great duty as conceived by an astonishing number of able men, brave and good, as well as of other sorts of men, is to hate “niggers.”

Not that this double disillusion has for a moment made black men doubt the wisdom of their wholehearted help of the Allies. Given the chance again, they would again do their duty—for have they not seen and known France? But these young men see today with opened eyes and strained faces the true and hateful visage of the Negro problem in America.

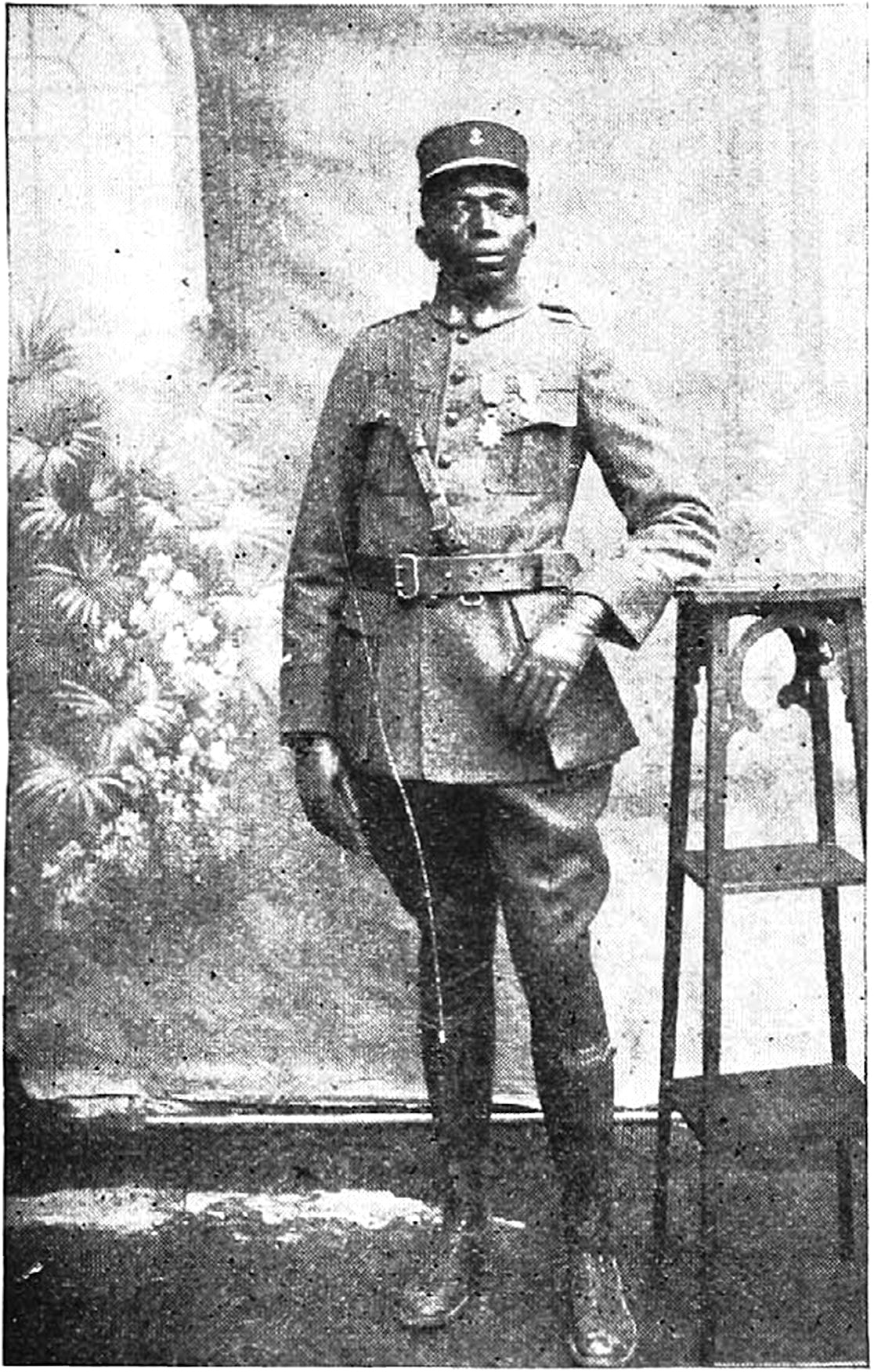

Lt. Bakane Diop, a Chief of the Senegalese and Chevalier of the Legion of Honor

Lt. Bakane Diop, a Chief of the Senegalese and Chevalier of the Legion of Honor

When the German host—grey, grim, irresistible, poured through Belgium, out of Africa France called her sons; they came; 280,000 black Senegalese, first and last—volunteers, not drafted; they hurled the Boches back across the Ourcq and the Marne on a ghastly bridge of their own dead. It was The Crisis—four long, bitter years the war wore on; but Germany was beaten at the first battle of the Marne, and by Negroes. Beside the Belgians, too, stood, first and last, 30,000 black Congolese, not to mention the 20,000 black English West Indians who fought in the East and the thousands of black troops who conquered German Africa.

Stevedores

But the story of stories is that of the American Negro. Here was a man who bravely let his head go where his heart at first could not follow, who for the first time as a nation within a nation did his bitter duty because it was his duty, knowing what might be expected, but scarcely foreseeing the whole truth.

We gained the right to fight for civilization at the cost of being “Jim-Crowed” and insulted; we were segregated in the draft; we were segregated in the first officers’ training camp; and we were allowed to volunteer only as servants in the Navy and as common laborers in the Army, outside of the four regular Negro regiments. The Army wanted stevedores, road builders, wood choppers, railroad hands, etc., and American Negroes were among the first to volunteer. Of the 200,000 Negroes in the American Expeditionary Force, approximately 150,000 were stevedores and laborers, doing the hardest work under, in some cases, the most trying conditions faced by any soldiers during the war. And it is the verdict of men who know that the most efficient and remarkable service has been rendered by these men. Patient, loyal, intelligent, not grouchy, knowing all that they were up against among their countrymen as well as the enemy, these American black men won the war as perhaps no other set of S.O.S. men of any other race or army won it.

Where were these men stationed? At some English ports; at many of the interior depots and bases; at the various France and in places where automobiles, airplanes, cars and locomotives were got ready for use; in the forests, on the mountains and in the valleys, cutting wood; building roads from ports of entry right up to the view and touch of Germans in the front-lines; burying the dead; salvaging at great risk to their own lives millions of shells and other dangerous war material, actually piling up and detonating the most deadly devices in order that French battlefields might be safe to those who walk the ways of peace.

Who commanded these thousands of black men assembled from all parts of the United States and representing in culture all the way from absolute illiterates from under-taught Southern States to well-educated men from northern universities and colleges and even from many northern universities and colleges? By a queer twist of American reasoning on the Negro it is assumed that he is best known and best “handled” by white people from the South, who more than any other white people refuse and condemn that sort of association that would most surely acquaint the white man with the very best that is in the Negro. Therefore, when officers were to be chosen for the Negro S.O.S. men, it seems that there was a preference expressed or felt for southern white officers. Some of these were fine men, but the majority were “nigger” drivers of the most offensive type.

The big, outstanding fact about the command of these colored soldiers is that southern men of a narrow, harsh type dictated the policy and method and so forced it that it became unpopular for officers to be generous to these men. When it is considered that these soldiers were abjectly under such men, with no practical opportunity for redress, it is easy to imagine the extremes to which harsh treatment could be carried. So thoroughly understood was it that the Negro had to be “properly handled and kept in his place,” even in France, large use was made even of the white non-commissioned officer so that many companies and units of Negro soldiers had no higher Negro command than corporal. This harsh method showed itself in long hours, excessive tasks, little opportunity for leaves and recreation, holding of black soldiers to barracks when in the same community white soldiers had the privilege of the town, severe punishments for slight offenses, abusive language and sometimes corporal punishment. To such extremes of “handling niggers” was this carried that Negro Y.M.C.A. secretaries were refused some units on the ground, frankly stated by officers, that it would be better to have white secretaries, and in many places separate “Y” huts were demanded for white and colored soldiers so that there would be no association or fraternizing between the races.

Worked often like slaves, twelve and fourteen hours a day, these men were well-fed, poorly clad, indifferently housed, often beaten, always “Jim-Crowed” and insulted, and yet they saw the vision—they saw a nation which splendid people threatened and torn by a ruthless enemy; they saw a democracy of splendid could not understand color prejudice. They received a thousand little kindnesses and half-known words of sympathy from the puzzled French, and French law and custom stepped in repeatedly to protect them, so that their only regret was the average white American. But they worked—how they worked! Everybody joins to testify to this: the white slave-drivers, the army officers, the French, the visitors—all say that the American Negro was the best laborer in France, of all the world’s peoples gathered there; and if American food and materials saved France in the end from utter exhaustion, it was the Negro stevedore who made that aid effective.

The 805th

To illustrate the kind of work which the stevedore and pioneer regiments did, we cite the history of one of the pioneer Negro regiments: Under the act of May 18, 1917, the President ordered the formation of eight colored infantry regiments. Two of these, the 805th and 806th, were organized at Camp Funston. The 805th became a Pioneer regiment and when it left camp had 3,526 men and 99 officers. It included 25 regulars from the 25th Infantry of the Regular Army, 38 mechanics from Prairie View, 20 horse-shoers from Tuskegee and 8 carpenters from Howard. The regiment was drilled and had target practice. The regiment proceeded to Camp Upton late in August, 1918, and sailed, a part from Montreal and a part from Quebec, Canada, early in September. Early in October the whole regiment arrived in the southern end of the Argonne forest. The men began their work of repairing roads as follows:

- First 2,000 meters of Clermont-Neuilly road from Clermont road past Apremont;

- Second 2,000 meters of Clermont-Neuilly road, Charpentry cut-off road;

- Lechères crossroad on Clermont-Neuilly road, north 2,000 meters, roads at Véry;

- Clermont-Neuilly road from point 1,000 south of Neuilly, bridge to Neuilly, ammunition detour road at Neuilly, Charpentry roads;

- Auzéville railhead, Varennes railhead; railhead work at St. Juvin and Briequenay;

- Auzéville railhead, Varennes railhead, roads at Montblainville, roads at Landres-et St. George;

- Roads at Avocourt, roads at Sommarenec;

- Roads at Avocourt, roads at Fleville;

- Construction of ammunition dump, Neuilly, and railhead construction between Neuilly and Varennes and Aprémont, railroad repair work March and St. Juvin, construction of Verdun-Etain railroad from November 11;

- Railhead details and road work Aubreville, road work Varennes and Charpentry;

- Road and railhead work Aubreville, road work Varennes.

The outlying companies were continually in immediate sight of the sausage balloons and witnessed many an air battle. Raids were frequent.

A concentration had been ordered at Varennes, November 18, and several companies had taken up their abode there or at Camp Mahaut, but to carry out the salvage program, a re-distribution over the Argonne-Meuse area had to be affected immediately.

The area assigned the 805th Pioneer Infantry extended from Boult-aux-Bois, almost due south to a point one kilometer west of Les Islettes; thence to Aubreville and Avocourt and Esnes; thence to Montfaucon via Bethincourt and Cuisy; thence north through Nantillois and Cunel to Bantheville; thence southwest through Romagne, Gesnes and Exermont to the main road just south of Fleville; and then north to Boult-aux-Bois through Fleville, St. Juvin, Grand Pré and Briquenay.

The area comprised all of the Argonne forest, from Clermont north and the Varennes-Malancourt-Montfaucon-Romagne sections. More than five hundred square miles of battlefield was included.

A list of the articles to be salvaged would require a page. Chiefly they were Allied and enemy weapons and cannon, web and leather equipment, clothing and blankets, rolling stock, aviation electrical and engineer equipment. It was a gigantic task and did not near completion until the first week in March when more than 3,000 French carloads had been shipped.

For some weeks truck transportation was scarce and work was slow and consisted largely in getting material to roadsides.

As companies of the 805th neared the completion of their areas they were put to work at the railheads where they helped load the salvage they had gathered and that which many other organizations of the area had brought, and sent it on its way to designated depots.

With the slackening of the salvage work, the regiment found a few days when it was possible to devote time to drilling, athletics and study. School and agricultural books were obtained in large numbers and each company organized classes which, though not compulsory, were eagerly attended by the men.

Curtailment of this work was necessitated by instructions from Advance Section Headquarters to assist in every way possible the restoration of French farmlands to a point where they could be cultivated.

This meant principally the filling of trenches across fields and upon this work the regiment entered March 15 with all its strength, except what was required for the functioning of the railheads not yet closed.

There was up to this time no regimental band.

At Camp Funston instruments had been requisitioned, but had not arrived before the regiment left. Efforts were made to enlist a colored band at Kansas City whose members wished to enter the Army as a band and be assigned to the 805th Pioneer Infantry. General Wood approved and took the matter up with the War Department. Qualified assent was obtained, but subsequent rulings prevented taking advantage of it, in view of the early date anticipated for an overseas move.

The rush of events when the regiment reached Europe precluded immediate attention being given the matter and, meanwhile, general orders had been issued against equipping bands not in the Regular Army.

Left to itself, without divisional connections, the regiment had to rely upon its own resources for diversion. The men needed music after the hard work they were doing and Colonel Humphrey sent his Adjutant to Paris to present the matter to the Y.M.C.A., Knights of Columbus and Red Cross.

The Red Cross was able to respond immediately and Captain Bliss returned January 1, 1919, with seven cornets, six clarinets, five saxophones, four slide trombones, four alto horns, two bass tubas, two baritones and a piccolo and, also, some “jazz band effects.”

The band was organized on the spot and as more instruments and music were obtained, eventually reached almost its tabular strength while it reached proficiency almost over night.

The following commendation of the work of the regiment was received:

The Chief Engineer desires to express his highest appreciation to you and to your regiment for the services rendered to the 1st Army in the offensive between the Meuse and the Argonne, starting September 26, and the continuation of that offensive on November 1 and concluding with the Armistice of November 11.

The success of the operations of the Army Engineer Troops toward constructing and maintaining supply lines, both roads and railway, of the Army was in no small measure made possible by the excellent work performed by your troops.

It is desired that the terms of this letter be published to all the officers and enlisted men of your command at the earliest opportunity.

A soldier writes us: > Our regiment is composed of colored and white officers. You will find a number of complimentary things on the regiment’s record in the Argonne in the history. We were, as you know, the fighting reserves of the Army and that we were right on this front from September to November 11. We kept the lines of communication going and, of course, we were raided and shelled by German long-range guns and subject to gas raids, too.

>

> We are now located in the Ardennes, between the Argonne and the Meuse. This is a wild and wooly forest, I assure you. We are hoping to reach our homes in May. We have spent over seven months in this section of the battle-front and we are hoping to get started home in a few weeks after you get this letter, at least. Our regiment is the best advertised regiment in the A. E. F. and its members are from all over the United States practically.

>

> A month or so ago we had a pay-day here and twenty thousand dollars was collected the first day and sent to relatives and banks in the United States. Every day our mail sergeant sends from one hundred to one thousand dollars per day to the United States for the men in our regiment,—savings of the small salary they receive as soldiers. As a whole they are and have learned many things by having had this great war experience.

Negro Officers

All this was expected. America knows the value of Negro labor. Negroes knew that in this war as in every other war they would have the drudgery and the dirt, but with set teeth they determined that this should not be the end and limit of their service. They did not make the mistake of seeking to escape labor, for they knew that modern war is mostly ordinary toil; they even took without protest the lion’s share of the common labor, but they insisted from the first that black men must serve as soldiers and officers.

The white Negro-hating oligarchy was willing to have some Negro soldiers—the privilege of being shot in real war being one which they were easily persuaded to share—provided these black men did not get too much notoriety out of it. But against Negro officers they set their faces like flint.

The dogged insistence of the Negroes, backed eventually by the unexpected decision of Secretary Baker, encompassed the first defeat of this oligarchy and nearly one thousand colored officers were commissioned.

Immediately a persistent campaign began:

First, was the effort to get rid of Negro officers; second, the effort to discredit Negro soldiers; third, the effort to spread race prejudice in France; and fourth, the effort to keep Negroes out of the Regular Army.

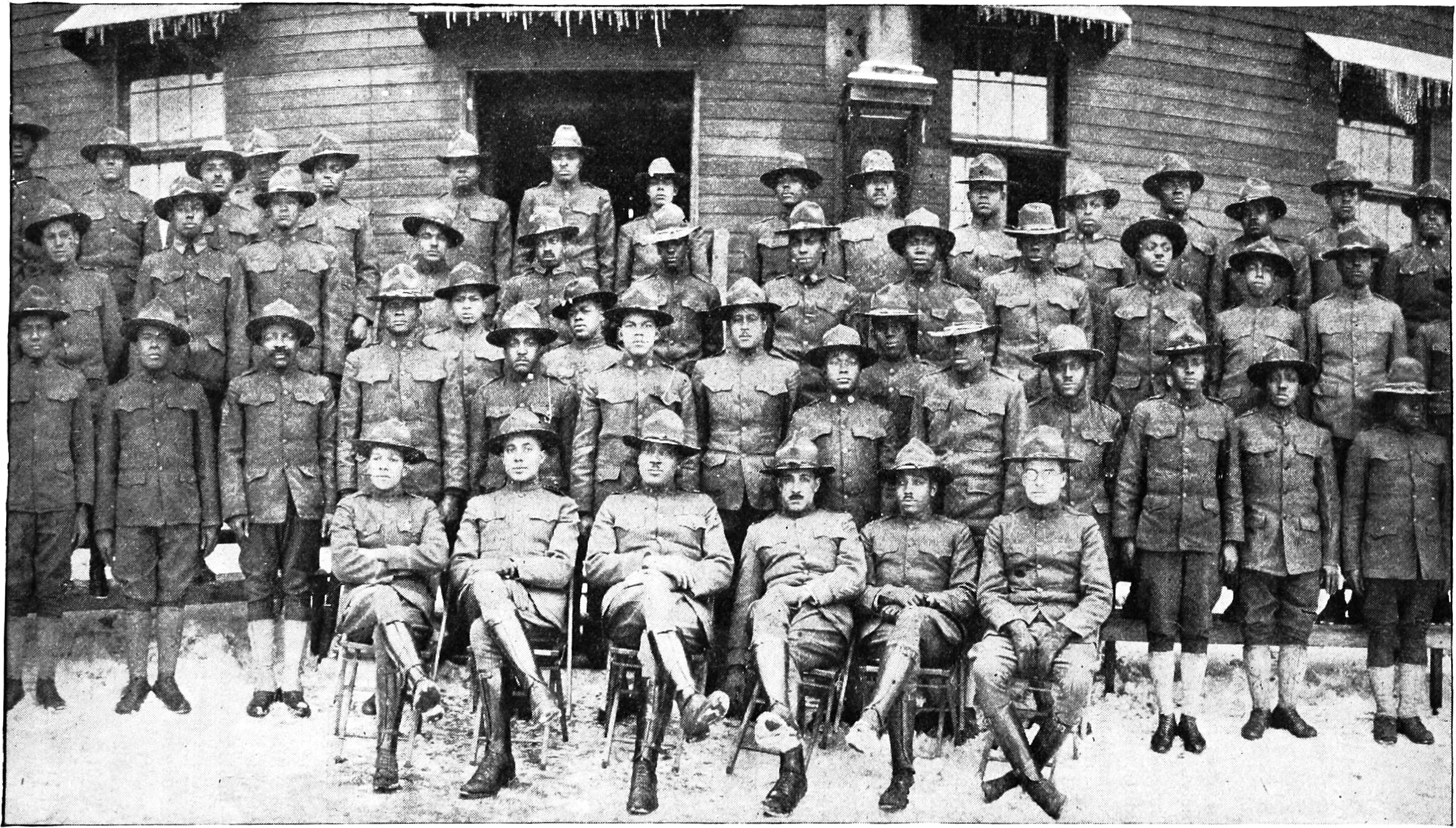

Company 22, Sixth Battalion, 163rd Depot Brigade, Camp Dodge, Iowa. The Only Unit in the Depot Brigades Entirely Officered by Negroes. Captain C. C. Cooper, and Lieutenants T. M. Gregory, E. S. Horne, J. E. Oliver, W. B. Hall and W. C. Dickerson.

Company 22, Sixth Battalion, 163rd Depot Brigade, Camp Dodge, Iowa. The Only Unit in the Depot Brigades Entirely Officered by Negroes. Captain C. C. Cooper, and Lieutenants T. M. Gregory, E. S. Horne, J. E. Oliver, W. B. Hall and W. C. Dickerson.

First and foremost, war is war and military organization is, and must be, tyranny. This is, perhaps, the greatest and most barbarous cost of war and the most pressing reason for its abolition from civilization. As war means tyranny, the company officer is largely at the mercy of his superior officers.

The company officers of the colored troops were mainly colored. The field officers were with very few exceptions white. The fate of the colored officers, therefore, depended almost absolutely on those placed in higher command. Moreover, American military trials and legal procedures are antiquated and may be grossly unfair. They give the accused little chance if the accuser is determined and influential.

The success, then, of the Negro troops depended first of all on their field officers; given strong, devoted men of knowledge and training there was no doubt of their being able to weed out and train company officers and organize the best body of fighters on the western front. This was precisely what the Negro-haters feared. Above all, they feared Charles Young.

Charles Young

There was one man in the United States Army who by every consideration of justice, efficiency and long, faithful service should have been given the command of a division of colored troops. Colonel Charles Young is a graduate of West Point and by universal admission is one of the best officers in the Army. He has served in Cuba, Haiti, the Philippines, Mexico, Africa and the West with distinction. Under him the Negro division would have been the most efficient in the Army. This rightful place was denied him. For a technical physical reason (“high blood pressure”) he was quickly retired from the Regular Army. He was not allowed a minor command or even a chance to act as instructor during the war.

On the contrary, the 92nd and 93rd Divisions of Negro troops were given commanding officers who with a half-dozen exceptions either distrusted Negroes or actively and persistently opposed colored officers under any circumstances. The 92nd Division particularly was made a dumping ground for poor and inexperienced field officers seeking promotion. A considerable number of these white officers from the first spent more time and ingenuity in making the lot of the Negro officer hard and the chance of the Negro soldier limited than in preparing to whip the Germans.

Prejudice

These efforts fell under various heads: giving the colored officers no instruction in certain lines and then claiming that none were fitted for the work, as in artillery and engineering; persistently picking the poorest Negro candidates instead of the best for examinations and tests so as to make any failure conspicuous; using court martials and efficiency boards for trivial offenses and wholesale removals of the Negroes; subjecting Negro officers and men to persistent insult and discrimination by refusing salutes, “Jim-Crowing” places of accommodation and amusement, refusing leaves, etc.; by failing to supply the colored troops with proper equipment and decent clothing; and finally by a systematic attempt to poison the minds of the French against the Negroes and compel them to follow the dictates of American prejudice.

These are serious charges. The full proof of them cannot be attempted here, but a few examples will serve to indicate the nature of the proof.

At the colored Officers’ Training Camp no instruction was given in artillery and a dead-line was established by which no one was commissioned higher than Captain, despite several recommendations. Certain Captains’ positions, like those of the Headquarters Companies, were reserved for whites, and former non-commissioned officers were given preference with the hope that they would be more tractable than college-bred men—a hope that usually proved delusive.

The colored divisions were never assembled as units this side of the water. General Ballou, a timid, changeable white man, was put in command of the 92nd Division and he antagonized it from the beginning.

General Ballou’s attitude toward the men of his command, as expressed in his famous, or rather infamous, Bulletin 35, which was issued during the period of training in the United States, was manifested throughout the division during the entire time that he was in command in France. Whenever any occasion arose where trouble had occurred between white and colored soldiers, the burden of proof always rested on the colored man. All discrimination was passed unnoticed and nothing was done to protect the men who were under his command. Previous to General Bullard’s suggestion that some order be issued encouraging the troops for the good work that they had done on the Vosges and Marbache fronts, there had been nothing done to encourage the men and officers, and it seemed that instead of trying to increase the morale of the division, it was General Ballou’s intention to discourage the men as much as possible. His action in censuring officers in the presence of enlisted men was an act that tended toward breaking down the confidence that the men had in their officers, and he pursued this method on innumerable occasions. On one occasion he referred to his division, in talking to another officer, as the “rapist division”; he constantly cast aspersion on the work of the colored officer and permitted other officers to do the same in his presence, as is evidenced by the following incident which took place in the office of the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, at Bourbon-les-Bains:

The staff had just been organized and several General Headquarters officers were at Headquarters advising relative to the organization of the different offices. These officers were in conversation with General Ballou, Colonel Greer, the Chief of Staff, Major Hickox, and Brigadier-General Hay. In the course of the conversation Brigadier-General Hay made the remark that “In my opinion there is no better soldier than the Negro, but God damn a ‘nigger’ officer!” This remark was made in the presence of General Ballou and was the occasion for much laughter.

After the 92d Division moved from the Argonne forest to the Marbache Sector the 368th Infantry was held in reserve at Pompey. It was at this place that General Ballou ordered all of the enlisted men and officers of this unit to congregate and receive an address to be delivered to them by him. No one had any idea as to the nature of this address; but on the afternoon designated, the men and officers assembled on the ground, which was used as a drill-ground, and the officers were severely censured relative to the operation that had taken place in the Argonne forest. The General advised the officers, in the presence of the enlisted men, that in his opinion they were cowards; that they had failed; and that “they did not have the guts” that made brave men. This speech was made to the officers in the presence of all of the enlisted men of the 368th Infantry and was an act contrary to all traditions of the Army.

When Mr. Ralph Tyler, the accredited correspondent of the War Department, reached the Headquarters of the 92d Division and was presented to General Ballou, he was received with the utmost indifference and nothing was done to enable him to reach the units at the front in order to gain the information which he desired. After Mr. Tyler was presented to General Ballou, the General walked out of the office of the Chief of Staff with Mr. Tyler, came into the office of the Adjutant, where all of the enlisted men worked, and stood directly in front of the desk of the colored officer, who was seated in the office of the Adjutant, and in a loud voice said to Mr. Tyler: “I regard the colored officer as a distinct failure. He is cowardly and has none of the traits which go to make a successful officer.” This expression was made in the presence of all of the enlisted personnel and in a tone of voice loud enough for all of them to hear.

General Ballou’s Chief of Staff was a white Georgian and from first to last his malign influence was felt and he openly sought political influence to antagonize his own troops.

General —— Commanding Officer of the —— (92d Division), said to Major Patterson, (color), Division Judge-Advocate, that there was a concerted action on the part of the white officers throughout France to discredit the work of the colored troops in France and that everything was being done to advertise those things that would reflect discredit upon the men and officers and to withhold anything that would bring to these men praise or commendation.

On the afternoon of November 8, the Distinguished Service Cross was awarded to Lieutenant Campbell and Private Bernard Lewis, 368th Infantry, the presentation of which was made with the prescribed ceremonies, taking place on a large field just outside of Villers-en-Haye and making a very impressive sight. The following morning a private from the 804th Pioneer Infantry was executed at Belleville, for rape. The official photographer attached to the 92d Division arose at 5 A.M. on the morning of the execution, which took place at 6 A.M., and made a moving-picture film of the hanging of this private. Although the presentation of the Distinguished Service Crosses occurred at 3 P. M. on the previous day, the official photographer did not see fit to make a picture of this and when asked if he had made a picture of the presentation, he replied that he had forgotten about it.

The campaign against Negro officers began in the cantonments. At Camp Dix every effort was made to keep competent colored artillery officers from being trained. Most of the Colonels began a campaign for wholesale removals of Negro officers from the moment of embarkation.

At first an attempt was made to have General Headquarters in France assent to the blanket proposition that white and Negro officers would not get on in the same organization; this was unsuccessful and was followed by the charge that Negroes were incompetent as officers. This charge was made wholesale and before the colored officers had had a chance to prove themselves, “Efficiency Boards” immediately began wholesale removals and as such boards could act on the mere opinion of field officers the colored company officers began to be removed wholesale and to be replaced by whites.

The court martials of Negro officers were often outrageous in their contradiction of common sense and military law. The experience of one Captain will illustrate. He was a college man, with militia training, who secured a captaincy at Des Moines—a very difficult accomplishment—and was from the first regarded as an efficient officer by his fellows; when he reached Europe, however, the Major of his battalion was from Georgia, and this Captain was too independent to suit him. The Major suddenly ordered the Captain under close arrest and after long delay preferred twenty-three charges against him. These he afterward reduced to seven, continuing meantime to heap restrictions and insults on the accused, but untried, officer. Instead of breaking arrest or resenting his treatment the Captain kept cool, hired a good colored lawyer in his division and put up so strong a fight that the court martial acquitted him and restored him to his command, and sent the Major to the stevedores.

Not every officer was able to preserve his calm and poise.

One colored officer turned and cursed his unfair superiors and the court martial, and revealed an astonishing story of the way in which he had been hounded.

A Lieutenant of a Machine Gun Battalion was employed at Intelligence and Personnel work. He was dismissed and reinstated three times because the white officers who succeeded him could not do the work. Finally he was under arrest for one and one-half months and was dismissed from service, but General Headquarters investigated the case and restored him to his rank.

Most of the Negro officers had no chance to fight. Some were naturally incompetent and deserved demotion or removal, but these men were not objects of attack as often as the more competent and independent men.

Here, however, as so often afterward, the French stepped in, quite unconsciously, and upset careful plans. While the American officers were convinced of the Negro officers’ incompetency and were besieging General Headquarters to remove them en masse, the French instructors at the Gondrecourt Training School, where Captains and selected Lieutenants were sent for training, reported that the Negroes were among the best Americans sent there.

Moreover, the 93d Division, which had never been assembled or even completed as a unit and stood unrecognized and unattached, was suddenly called in the desperate French need, to be brigaded with French soldiers. The Americans were thoroughly scared. Negroes and Negro officers were about to be introduced to French democracy without the watchful eye of American color hatred to guard them. Something must be done.

As the Negro troops began moving toward the Vosges sector of the battlefield, August 6, 1918, active anti-Negro propaganda became evident. From the General Headquarters of the American Army at Chaumont the French Military Mission suddenly sent out, not simply to the French Army, but to all the Prefects and Sous-Prefects of France (corresponding to our governors and mayors), a data setting forth at length the American attitude toward Negroes; warning against social recognition; stating that Negroes were prone to deeds of violence and were threatening America with degeneration, etc. The white troops backed this propaganda by warnings and tales wherever they preceded the blacks.

This misguided effort was lost on the French. In some cases peasants and villagers were scared at the approach of Negro troops, but this was but temporary and the colored troops everywhere they went soon became easily the best liked of all foreign soldiers. They were received in the best homes, and where they could speak French or their hosts understood English, there poured forth their story of injustice and wrong into deeply sympathetic ears. The impudent swagger of many white troops, with their openly expressed contempt for “Frogs” and their evident failure to understand the first principles of democracy in the most democratic of lands, finished the work thus begun.

No sounding words of President Wilson can offset in the minds of thousands of Frenchmen the impression of disloyalty and coarseness which the attempt to force color prejudice made on a people who just owed their salvation to black West Africa!

Little was published or openly said, but when the circular on American Negro prejudice was brought to the attention of the French ministry, it was quietly collected and burned. And in a thousand delicate ways the French expressed their silent disapprobation. For instance, in a provincial town a colored officer entered a full dining-room; the smiling landlady hastened to seat him (how natural!) at a table with white American officers, who immediately began to show their displeasure. A French officer at a neighboring table with French officers quietly glanced at the astonished landlady. Not a word was said, no one in the dining-room took any apparent notice, but the black officer was soon seated with the courteous Frenchmen.

On the Negroes this double experience of deliberate and devilish persecution from their own countrymen, coupled with a taste of real democracy and world-old culture, was revolutionizing. They began to hate prejudice and discrimination as they had never hated it before. They began to realize its eternal meaning and complications. Far from filling them with a desire to escape from their race and country, they were filled with a bitter, dogged determination never to give up the fight for Negro equality in America. If American color prejudice counted on this war experience to break the spirit of the young Negro, it counted without its host. A new, radical Negro spirit has been born in France, which leaves us older radicals far behind. Thousands of young black men have offered their lives for the Lilies of France and they return ready to offer them again for the Sun-flowers of Afro-America.

The 93rd Division

The first American Negroes to arrive in France were the Labor Battalions, comprising all told some 150,000 men.

The Negro fighting units were the 92nd and 93rd Divisions.

The so-called 93rd Division was from the first a thorn in the flesh of the Bourbons. It consisted of Negro National Guard troops almost exclusively offered by Negroes—the 8th Illinois, the 15th New York, and units from the District of Columbia, Maryland, Ohio, Tennessee and Massachusetts. The division was thus incomplete and never really functioned as a division. For a time it was hoped that Colonel Young might be given his chance here, but nothing came of this. Early in April when the need of the French for re-enforcements was sorest, these black troops were hurriedly transported to France and were soon brigaded with the French armies.

The 369th

This regiment was originally authorized by Governor Sulzer, but its formation was long prevented. Finally it was organized with but one Negro officer. Eventually the regiment sailed with colored and white officers, landing in France, January 1, 1918, and went into the second battle of the Marne in July, east of Verdun, near Ville-sur-Turbe. It was thus the first American Negro unit in battle and one of the first American units. Colored officers took part in this battle and some were cited for bravery. Nevertheless the white Colonel, Hayward, after the battle secured the transfer of every single colored officer, except the bandmaster and chaplain.

The regiment was in a state of irritation many times, but it was restrained by the influence of the non-commissioned officers—very strong in this case because the regiment was all from New York and mainly from Harlem—and especially because being brigaded with the French they were from the first treated on such terms of equality and brotherhood that they were eager to fight. There were charges that Colonel Hayward and his white officers needlessly sacrificed the lives of these men. This, of course, is hard to prove; but certainly the casualties in this regiment were heavy and in the great attack in the Champagne, in September and October, two hundred were killed and eight hundred were wounded and gassed. The regiment went into battle with the French on the left and the Moroccans on the right and got into its own barrage by advancing faster than the other units. It was in line seven and one-half days, when three to four days is usually the limit.

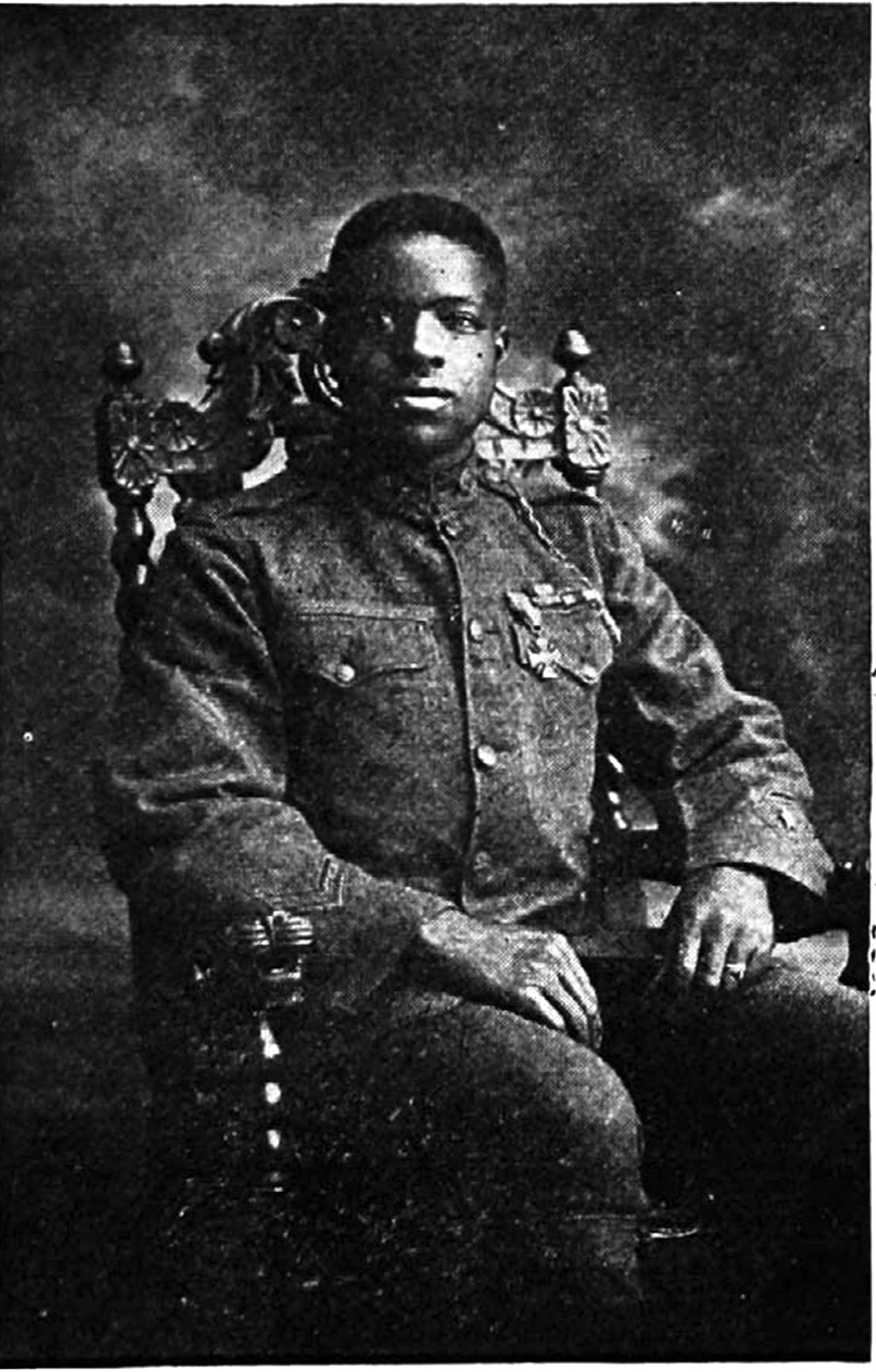

Sergeant E. W. Barringtine, 369th U.S.I., with French Medaille Militaire and Croix De Guerre.

Sergeant E. W. Barringtine, 369th U.S.I., with French Medaille Militaire and Croix De Guerre.

In all, the regiment was under fire 191 days—a record for any American unit. It received over 170 citations for the Croix de Guerre and Distinguished Service Cross and was the first unit of the Allied armies to reach the Rhine, November 18, with the Second French Army.

The 371st and 372nd

The 371st Regiment was drafted from South Carolina and had southern white officers from the first, many of whom were arrogant and overbearing. The regiment mobilized at Camp Jackson, October 5-17, and embarked for France, April 9, from Newport News, Va. It was trained at Rembercourt-aux-Ports (Meuse) and left for the region near Bar-le-Duc, June 5. The troops arrived in the Argonne June 22. They were brigaded with the 157th French Division, 13th Army Corps, and remained in the battle-line, front and reserve, until the Armistice was signed.

There are few data at present available for the history of this regiment because there were no colored officers to preserve it. It is rumored, however, that after the first battle the number of casualties among the meanest of their officers led to some mutual understandings. The regiment received a number of citations for bravery.

As this regiment was brigaded usually with the 372nd, a part of its history follows:

The official records show that the 372nd Infantry was organized at Camp Stuart, January 1, 1918, Colonel Glendie B. Young, Infantry, U.S.N.G., commanding, and included the following National Guard units: First Separate Battalion, District of Columbia, Infantry; Ninth Battalion of Ohio, Infantry; Company L, Sixth Massachusetts, Infantry; and one company each from Maryland, Tennessee and Connecticut. To these were added later 250 men from Camp Custer; excepting the Staff, Machine Gun, Headquarters and Supply Companies, the regiment was officered by colored men.

The regiment was brigaded with the 371st into the 186th Infantry Brigade, a unit of the Provisional 93rd Division. It was understood that the 93rd Division, which was to be composed of all Negro troops, would be fully organized in France; but when the 372nd arrived at St. Nazaire, April 14, 1918, the organization was placed under command of the French. Four weeks later the brigade was dissolved and the 93rd Division ceased to be mentioned. Its four regiments were all subject to orders of the French G.Q., General Petain, commanding.

The regiment spent five weeks in training and re-organization at Conde-en-Barrois (Meuse), as a unit of the 13th French Army Corps. The men were trained in French methods by French officers and non-commissioned officers with French ordnance equipment. They developed so rapidly that a French Major exclaimed enthusiastically on the street: “These men are intelligent and alert. Their regiment will have a glorious career.” Thus, from the beginning the worth of our troops was recognized by a veteran of the French Army.

To complete its training under actual war conditions, the regiment was sent to a “quiet sector”—sub-sector, Argonne West, on June 8, where it spent twenty days learning the organization of defensive positions and how to hold these positions under shell fire from the enemy. During this time it was a part of the 63rd French Division and during the last ten days it was a part of the 35th French Division. On July 2, the 372nd Infantry became permanently identified with the 157th French Division, commanded by General Goybet. The division consisted of two colored American regiments and one French regiment of infantry. The artillery units, engineers, sanitary train, etc., were all French. On his first inspection tour, at Vanquois, General Goybet asked one of our men if he thought the Germans could pass if they started over. The little brown private replied: “Not if the boches can’t do a good job in killing all of us.” That pleased the new General very much and clinched his confidence in the black troops.

On July 13 the regiment retired to a reserve position near the village of Locheres (Meuse), for temporary rest and to help sustain the coming blow. The next day Colonel Young was relieved of command by Colonel Herschel Tupes, a regular army officer. In the afternoon the regiment was assembled and prepared for action, but it later was found that it would not be needed. The attack of the Germans was launched near Rheims on the night of July 14 and the next evening the world read of the decisive defeat of the Germans by General Gourand’s army.

The following Sunday found the regiment billeted in the town of Sivry-la-Perche, not very far from Verdun. After a band concert in the afternoon Colonel Tupes introduced himself to his command. In the course of his remarks, he said that he had always commanded regulars, but he had little doubt that the 372nd Infantry could become as good as any regiment in France.

On July 26 the regiment occupied sub-sector 304. The occupation of this sub-sector was marked by hard work and discontentment. The whole position had to be re-organized, and in doing this the men maintained their previous reputation for good work. The total stay in the sector was seven weeks. The regiment took part in two raids and several individuals distinguished themselves: one man received a Croix de Guerre because he held his trench mortar between his legs to continue firing when the base had been damaged by a shell; another carried a wounded French comrade from “No Man’s Land” under heavy fire, and was also decorated. Several days after a raid, the Germans were retaliating by shelling the demolished village of Montzeville, situated in the valley below the Post-of-Command and occupied by some of the reserves; Private Rufus Pinckney rushed through the heavy fire and rescued a wounded French soldier.

On another occasion, Private Kenneth Lewis of the Medical Detachment, later killed at his post, displayed such fine qualities of coolness and disdain for danger by sticking to duty until the end that two post-mortem decorations: the Croix de Guerre with Palm and Medaille Militaire were awarded. The latter is a very distinguished recognition in the French Army.

So well had the regiment worked in the Argonne that it was sent to relieve the 123rd French Infantry Regiment in the sub-sector Vanquois, on July 28. An attack by the Germans in the valley of the Aire, of which Vanquois was a key, was expected at any moment. New defenses were to be constructed and old ones strengthened. The men applied themselves with a courageous devotion, night and day, totheir tasks and after two weeks of watchful working under fire, Vanquois became a formidable defensive system.

Besides the gallantry of Private Pinckney, Montzeville must be remembered in connection with the removal of colored officers from the regiment. It was there that a board of officers (all white) requested by Colonel Young and appointed by Colonel Tupes, sat on the cases of twenty-one colored officers charged with inefficiency. Only one out of that number was acquitted: he was later killed in action. The charges of inefficiency were based on physical disability, insufficient training, unsuitability. The other colored officers who had been removed were either transferred to other units or sent to re-classification depots.

The Colonel told the Commanding General through an interpreter: “The colored officers in this regiment know as much about their duties as a child.” The General was surprised and whispered to another French officer that the Colonel himself was not so brilliant and that he believed it was prejudice that caused the Colonel to make such a change. A few moments after, the Colonel told the General that he had requested that no more colored officers be sent to the regiment. In reply to this the General explained how unwise it was because, the colored officers had been trained along with their men at a great expenditure of time and money by the American and French governments; and, also, he doubted if well-qualified white officers could be spared him from other American units. The General insisted that the time was at hand for the great autumn drive and that it would be a hindrance because he feared the men would not be pleased with the change. The Colonel heeded not his General and forwarded two requests for an anti-colored-officer regiment. He went so far as to tell the Lieutenant-Colonel that he believed the regiment should have white men for non-commissioned officers. Of course, the men would not have stood for this at any price. The Colonel often would tell the Adjutant to never trust a “damned black clerk” and that he considered “one white man worth a million Negroes.”

About September 8 the regiment was relieved by the 129th United States Infantry and was sent to the rear for a period of rest. Twenty-four hours after arrival in the rest area, orders were received to proceed farther. The nightly marches began. The regiment marched from place to place in the Aube, the Marne and the Haute Marne until it went into the great Champagne battle on September 27.

For nine days it helped push the Hun toward the Belgian frontier. Those days were hard, but these men did their duty and came out with glory. Fortunately, all the colored officers had not left the regiment and it was they and the brave sergeants who led the men to victory and fame. The new white officers had just arrived, some of them the night before the regiment went into battle, several of whom had never been under fire in any capacity, having just come out of the training school at Langres. Nevertheless, the regiment was cited by the French and the regimental colors were decorated by Vice-Admiral Moreau at Brest, January 24, 1919.

After the relief on the battlefield, the regiment reached Somme Bionne (Marne) October 8. Congratulations came in from everywhere except American Headquarters. After a brief rest of three days the regiment was sent to a quiet sector in the Vosges, on the frontier of Alsace. The Colonel finally disposed of the remaining colored officers, except the two dentists and the two chaplains. All the officers were instructed to carry their arms at all times and virtually to shoot any soldier on the least provocation.

As a consequence, a corporal of Company L was shot and killed by First Lieutenant James B. Coggins, from North Carolina, for a reason that no one has ever been able to explain. The signing of the Armistice and the cessation of hostilities, perhaps, prevented a general, armed opposition to a system of prejudice encouraged by the Commanding Officer of the Regiment.

Despite the prejudice of officers toward the men, the regiment marched from Ban-de-Laveline to Granges of Vologne, a distance of forty-five kilometers, in one day and maintained such remarkable discipline that the officers themselves were compelled to accord them praise.

While stationed at Granges, individuals in the regiment were decorated on December 17 for various deeds of gallantry in the Champagne battle. General Goybet presented four military medals and seventy-two Croix de Guerre to enlisted men. Colonel Tupes presented four Distinguished Service Crosses to enlisted men. At the time, the regiment had just been returned to the American command, the following order was read:

157th Division

Hqrs. December 15th, 1918.

Staff.

General Order No. 246.

On the date of the 12th of December, 1918, the 371st and the 372nd R.I., U.S. have been returned to the disposal of the American Command. It is not without profound emotion that I come in the name of the 157th (French) Division and in my personal name, to say good-bye to our valiant comrades of combat. For seven months we have lived as brothers of arms, sharing the same works, the same hardships, the same dangers; side by side we have taken part in the great battle of the Champagne, that a wonderful victory has ended.

The 157th (French) Division will never forget the wonderful impetus irresistible, the rush heroic of the colored American regiments on the “Observatories Crest” and in the Plain of Menthois. The most formidable defense, the nests of machine guns, the best organized positions, the artillery barrages most crushing, could not stop them. These best regiments have gone through all with disdaining of death and thanks to their courage devotedness, the “Red Hand” Division has during nine hard days of battle been ahead in the victorious advance of the Fourth (French) Army.

Officers and non-commissioned officers and privates of the 371st and 372nd Regiments Infantry, U.S., I respectfully salute your glorious dead and I bow down before your standards, which by the side of the 333rd R.I., led us to victory.

Dear Friends from America, when you have crossed back over the ocean, don’t forget the “Red Hand” Division. Our fraternity of arms has been soaked in the blood of the brave. Those bonds will be indistructible.

Keep a faithful remembrance to your General, so proud to have commanded you, and remember that his thankful affection is gained to you forever.

(Signed) General Goybet, Commanding the 157th. (French) Division, Infantry.

Colonel Tupes, in addressing the regiment, congratulated them on the achievements and expressed his satisfaction with their conduct. He asked the men to take a just pride in their accomplishments and their spirit of loyalty.

Can this be surpassed for eccentricity?

The seven weeks at Granges were pleasant and profitable socially. Lectures were given to the men by French officers, outdoor recreation was provided and the civilian population opened their hearts and their homes to the Negro heroes. Like previous attempts, the efforts of the white officers to prevent the mingling of Negroes with the French girls of the village were futile. Every man was taken on his merits. The mayor of Granges gave the regiment an enthusiastic farewell.

On January 1, 1919, the regiment entrained for Le Mans (Sarthe). After completing with the red-tape preparatory to embarkation and the delousing process it went to Brest, arriving there January 13, 1919.

The 370th

Up to this point the anti-Negro propaganda is clear and fairly consistent and unopposed. General Headquarters had not only witnessed instructions in Negro prejudice to the French, but had, also, consented to wholesale removals of officers among the engineers and infantry, on the main ground of color. Even the French, in at least one case, had been persuaded that Negro officers were the cause of certain inefficiencies in Negro units.

Undoubtedly the cruel losses of the 369th Regiment were due in part to the assumption of the French at first that the American Negroes were like the Senegalese; these half-civilized troops could not in time given them be trained in modern machine warfare, and they were rushed at the enemy almost with naked hands. The resulting slaughter was horrible. Our troops tell of great black fields of stark and crimson dead after some of these superhuman onrushes.

It was this kind of fighting that the French expected of the black Americans at first and some white American officers did not greatly care so long as white men got the glory. The French easily misunderstood the situation at first and assumed that the Negro officers were to blame, especially as this was continually suggested to them by the Americans.

It was another story, however, when the 370th Regiment came. This was the famous 8th Illinois, and it had a full quota of Negro officers, from Colonel down. It had seen service on the Mexican Border; it went to Houston, Tex., after the Thirteen had died for Freedom; and it was treated with wholesome respect. It was sent to Newport News, Va., for embarkation; one Colonel Denison refused to embark his troops and marched them back to camp because he learned they were to be “Jim-Crowed” on the way over.

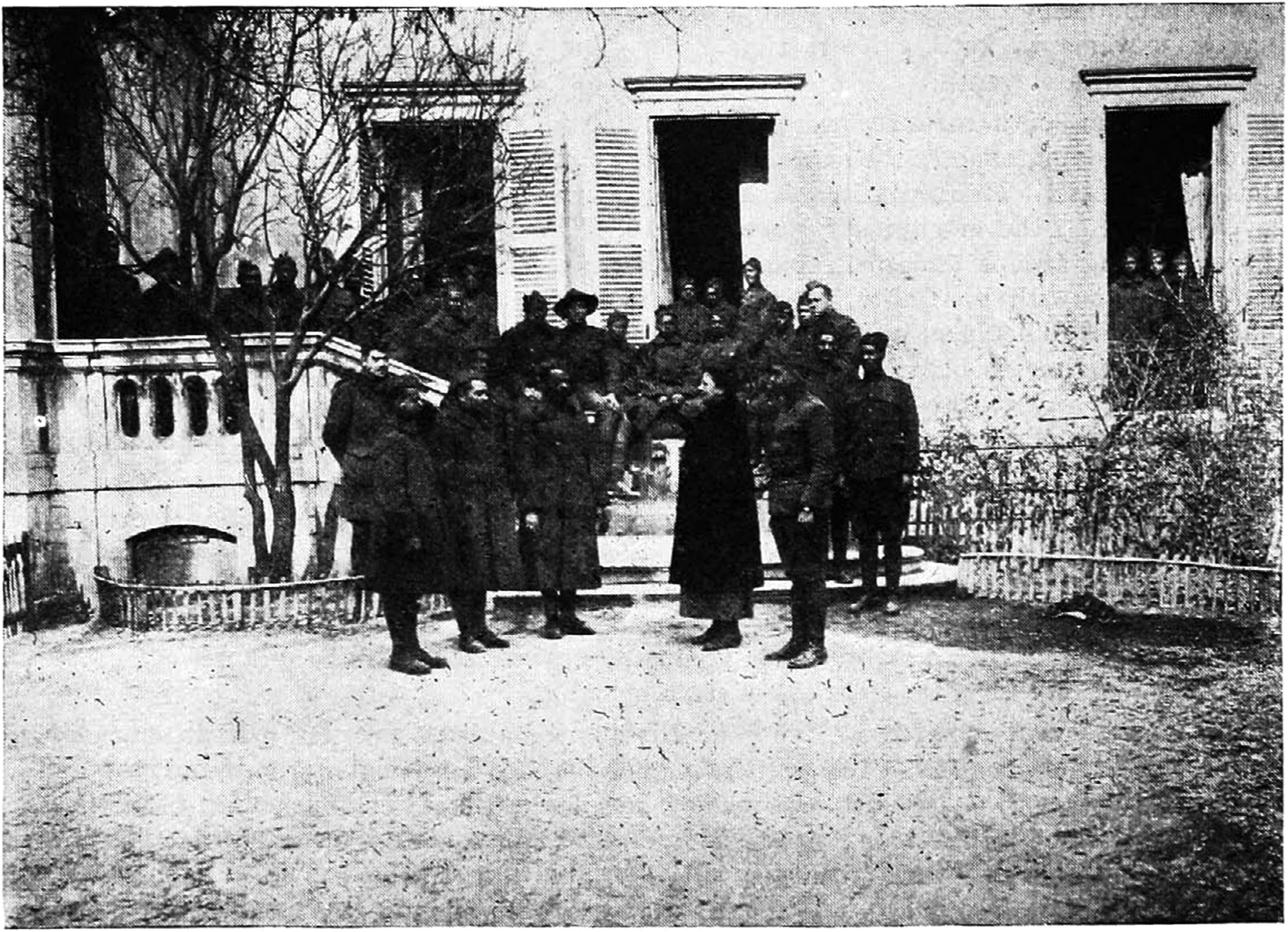

The Colonel and Officers of the 370th U. S. I. with Captain Boutte and Dr. Du Bois in camp at Le Mans, France.

The Colonel and Officers of the 370th U. S. I. with Captain Boutte and Dr. Du Bois in camp at Le Mans, France.

The regiment arrived at Brest, April 22, and was assigned to the 72nd French Division, remaining near Belfort until June 17. Then it went with the 34th French Division into the front-line, at St. Mihiel, for a month and later with the 36th French Division into the Argonne, where they fought. They were given a short period of rest and then they went into the front-line, at Soissons, with the 59th French Division. In September and October they were fighting again.

On September 15, in the Vauxaillon area, they captured Mt. Des singes and the adjacent woods after severe fighting. They held a sector alone afterward on the Canal L’Oise et Aisne and when attacked, repulsed the Germans and moved forward, gaining the praise of the French General. On October 24, the regiment went into the front-line again, near Grand Lup, and performed excellent service; the Armistice found part of the regiment across the Belgian frontier.

The general conduct of the regiment was excellent. No case of rape was reported and only one murder. The regiment received sixteen Distinguished Service Crosses and seventy-five Croix de Guerre, beside company citations.

When at first the regiment did not adopt the tactics of “shock” troops, the white Americans again took their cue and inspired a speech from the French General, which the colored men could not understand. It was not long, however, before the French General publicly apologized for his first and hasty criticism and afterward he repeatedly commended both officers and men for their bravery, intelligence and daring. This regiment received more citations than any other American regiment for bravery on the field of battle. There was, of course, the fly in the ointment—the effort to substitute white officers was strong and continuous, notwithstanding the fact that many of the black officers of this regiment were among the most efficient in the American Army.

General Headquarters by this time had begun to change its attitude and curb the Bourbons. It announced that it was not the policy of the American Army to make wholesale removals simply on account of color and it allowed the citations for bravery of Negro troops to be approved.

Nevertheless, the pressure continued. First the colored Colonel, the ranking Negro officer in France, was sent home. The reason for this is not clear. At any rate Colonel Dennison was replaced by a white Colonel, who afterward accepted a Croix de Guerre for an exploit which the Negro officers to a man declare was actually performed by a Negro officer while he was sitting snugly in his tent. The men of the regiment openly jeered him, crying out: “Blue Eyes ain’t our Colonel; Duncan’s our Colonel!” referring to the colored Lieutenant-Colonel. But the white Colonel was diplomatic; he let the colored officers run the regiment, posed as the “Moses” of the colored race (to the open amusement of the Negroes) and quietly tried to induct white officers. “I cannot understand why they sent this white Lieutenant,” he said plaintively to a colored officer. The officer at that moment had in his pocket a copy of the Colonel’s telegram asking General Headquarters for white officers. But the Armistice came before the Colonel succeeded in getting but two white officers,—his brother as Major (without a battalion) and one Lieutenant.

The organization that ranked all America in distinction remained, therefore, a Negro organization, for the white Colonel was only “commanding” and Dennison was still titular head.

The 92nd Division

So much for the 93rd Division. Its troops fought magnificently in the Champagne, the Argonne and elsewhere and were given unstinted praise by the French and even commendation by the Americans. They fought well, too, despite the color of their officers—371st Regiment under white, the 369th and 372nd Regiments under white and colored, and the 370th Regiment under colored were equally brave, except that the 370th Regiment made the most conspicuous record.

One might conclude under ordinary circumstances that it was a matter of efficiency in officers and not of race, but, unfortunately, the efficient colored officer had almost no chance even to try except in the 370th Regiment and in the Champagne battle with the 372nd Regiment. With a fair chance there is no doubt that he could have led every one of these regiments just as well as the white officers. It must, too, be remembered that all the non-commissioned officers in all these regiments were Negroes.

The storm center of the Negro troops was the 92nd Division. The brigading of the 93rd Division with the French made wholesale attack and depreciation difficult, since it was continually annulled by the generous appreciation of the French. The 92nd Division, however, was planned as a complete Negro division, manned by Negro company officers. Everything depended, then, on the General and field officers as to how fair this experiment should be.

From the very first there was open and covert opposition and trouble. Instead of putting Colonel Young at the head, the white General Ballou, was chosen and surrounded by southern white officers who despised “nigger” officers.

General Ballou himself was well-meaning, but weak, vacillating, without great ability and afraid of southern criticism. He was morbidly impressed by the horror of this “experiment” and proceeded from the first to kill the morale of his troops by orders and speeches. He sought to make his Negro officers feel personal responsibility for the Houston outbreak; he tried to accuse them indirectly of German propaganda; he virtually ordered them to submit to certain personal humiliations and discriminations without protest. Thus, before the 92nd Division was fully formed, General Ballou had spread hatred and distrust among his officers and men. “That old Ballou stuff!” became a by-word in the division for anti-Negro propaganda. Ballou was finally dismissed from his command for “tactical inefficiency.”

The main difficulty, however, lay in a curious misapprehension in white men of the meaning and method of race contact in America. They sought desperately to reproduce in the Negro division and in France the racial restrictions of America, on the theory that any new freedom would “spoil” the blacks. But they did not understand the fact that men of the types who became Negro officers protect themselves from continuous insult and discrimination by making and moving in a world of their own; they associate socially where they are more than welcome; they live for the most part beside neighbors who like them; they attend schools where they are not insulted; and they work where their work is appreciated. Of course, every once in a while they have to unite to resent encroachments upon their world—new discriminations in law and custom; but this is occasional and not continuous.

The world which General Ballou and his field officers tried to re-create for Negro officers was a world of continuous daily insult and discrimination to an extent that none had ever experienced, and they did this in a country where the discrimination was artificial and entirely unnecessary, arousing the liveliest astonishment and mystification.

For instance, when the Headquarters Company of the 92nd Division sailed for Brest, elaborate quarters in the best hotel were reserved for white officers, and unfinished barracks, without beds and in the cold and mud, were assigned Negro officers. The colored officers went to their quarters and then returned to the city. They found that the white Americans, unable to make themselves understood in French, had not been given their reservation, but had gone to another and poorer hotel. The black officers immediately explained and took the fine reservations.

As no Negroes had been trained in artillery, it was claimed immediately that none were competent. Nevertheless, some were finally found to qualify. Then it was claimed that technically trained privates were impossible to find. There were plenty to be had if they could be gathered from the various camps. Permission to do this was long refused, but after endless other delays and troubles, the Field Artillery finally came into being with a few colored officers. Before the artillery was ready, the division mobilized at Camp Upton, between May 28 and June 4, and was embarked by the tenth of June for France.

The entire 92nd Division arrived at Brest by June 20. A week later the whole division went to Bourbonne-les-Bains, where it stayed in training until August 6. Here a determined effort at wholesale replacement of the colored officers took place Fifty white Lieutenants were sent to the camp to replace Negro officers. “Efficiency” boards began to weed out colored men.

Without doubt there was among colored as among white American officers much inefficiency, due to lack of adaptability, training and the hurry of preparation. But in the case of the Negro officers repeatedly the race question came to the fore and permission was asked to remove them because they were colored, while the inefficiency charge was a wholesale one against their “race and nature.”

General Headquarters by this time, however, had settled down to a policy of requiring individual, rather than wholesale, accusation, and while this made a difference, yet in the army no officer can hold his position long if his superiors for any reason wish to get rid of him. While, then, many of the waiting white Lieutenants went away, the colored officers began to be systematically reduced in number.

On August 6 the division entered the front-line trenches in the Vosges sector and stayed here until September 20. It was a quiet sector, with only an occasional German raid to repel. About September 20, the division began to move to the Argonne, where the great American drive to cut off the Germans was to take place. The colored troops were not to enter the front-lines, as General Pershing himself afterward said, as they were entirely unequipped for front-line service. Nevertheless, the 368th Regiment, which arrived in the Argonne September 24, was suddenly sent into battle on the front-line on the morning of September 26. As this is a typical instance of the difficulties of Negro officers and troops, it deserves recital in detail.

It is the story of the failure of white field officers to do their duty and the partially successful and long-continued effort of company officers and men to do their duty despite this. That there was inexperience and incompetency among the colored officers is probable, but it was not confined to them; in their case the greater responsibility lay elsewhere, for it was the plain duty of the field officers: First, to see that their men were equipped for battle; second, to have the plans clearly explained, at least, step by step, to the company officers; third, to maintain liaison between battalions and between the regiment and the French and other American units.

Here follows the story as it was told to me point by point by those who were actually on the spot. They were earnest, able men, mostly Lieutenants and Captains, and one could not doubt, there in the dim, smoke-filled tents about Le Mans, their absolute conscientiousness and frankness.

The 368th

The 368th Regiment went into the Argonne September 24 and was put into the drive on the morning of September 26. Its duty was “combat liaison,” with the French 37th Division and the 77th (white) Division of Americans. The regiment as a whole was not equipped for battle in the front-line. It had no artillery support until the sixth day of the battle; it had no grenades, no trench fires, trombones, or signal flares, no airplane panels for signaling and no shears for German wire. The wire-cutting shears given them were absolutely useless with the heavy German barbed wire and they were able to borrow only sixteen large shears, which had to serve the whole attacking battalion.1 Finally, they had no maps and were at no time given definite objectives.

The Second Battalion of the 368th Regiment entered battle on the morning of September 26, with Major Elser in command; all the company officers were colored; Company F went “over the top” at 5:30 A.M.; Company H, with which the Major was, went “over” at 12:30 noon; advancing four kilometers further, the battalion met the enemy’s fire; the Machine Gun Company silenced the fire; Major Elser, who had halted in the woods to collect souvenirs from dead German bodies, immediately with drew part of the battalion to the rear in single file about dark without notifying the rest of the battalion. Captain Dabney and Lieutenant Powell of the Machine Gun Company led the rest of the men out in order about 10:00 P.M. When the broadside opened on September 26, Major Elser stood wringing his hands and crying: “What shall I do! What shall I do!” At night he deplored the occurrence, said it was all his fault, and the next morning Major Elser commended the Machine Gun Company for extricating the deserted part of the battalion. Moving forward again at 11 A. M., two companies went “over the top” at 4 P.M. without liaison. With the rest of the battalion again, these companies went forward one and one-half kilometers. Major Elser stayed back with the Post-of-Command. Enemy fire and darkness again stopped the advancing companies and Captain Jones fell back 500 metres and sent a message about 6 A.M. on the morning of September 28 to the Major asking for re-enforcements. Captain Jones stayed under snipers’ fire until about 3 P.M. and when no answer to his request came from the Major, he went “over the top” again and retraced the same 500 metres. Heavy machine gun and rifle fire again greeted him. He took refuge in nearby trenches, but his men began to drift away in confusion. All this time the Major was in the rear. On September 28, however, Major Elser was relieved of the command of the battalion and entered the hospital for “psycho-neurosis,” or “shell-shock,”—a phrase which often covers a multitude of sins. Later he was promoted to Lieutenant-Colonel and transferred to a Labor Battalion.

Meantime, on September 27, at 4:30 P.M., the Third Battalion of the 368th Infantry moved forward. It was commanded by Major B.F. Norris, a white New York lawyer, a graduate of Plattsburg, and until this battle a Headquarters Captain with no experience on the line. Three companies of the battalion advanced two and one-half kilometers and about 6:30 P.M. were fired on by enemy machine guns. The Major, who was in support with one company and a platoon of machine guns, ordered the machine guns to trenches seventy-five yards in the rear. The Major’s orders were confusing and the company as well as the platoon retreated to the trenches, leaving the firing-line unsupported. Subjected to heavy artillery, grenade, machine gun and rifle fire during the whole night of September 27 and being without artillery support or grenades, the firing line broke and the men took refuge in the trench with the Major, where all spent a terrible night under rain and bombardment. Next morning, September 28, at 7:30 A.M., the firing-line was restored and an advance ordered. The men led by their colored officers responded. They swept forward two and one-half kilometers and advanced beyond both French and Americans on the left and right. Their field officers failed to keep liaison with the French and American white units and even lost track of their own Second Battalion, which was dribbling away in one of the front trenches. The advancing firing-line of the Third Battalion met a withering fire of trench mortars, seventy-sevens, machine guns, etc. It still had no artillery support and being too far in advance received the German fire front, flank and rear and this they endured five hours. The line broke at 12:30 and the men retreated to the support trench, where the Major was. He reprimanded the colored officers severely. They reported the intense artillery fire and their lack of equipment, their ignorance of objectives and their lack of maps for which they had asked. They were ordered to re-form and take up positions, which they did. Many contradictory orders passed to the Company Commanders during the day: to advance, to halt, to hold, to withdraw, to leave woods as quickly as possible. Finally, at 6:30 P.M., they were definitely ordered to advance. They advanced three kilometres and met exactly the same conditions as before,—heavy artillery fire on all sides. The Company Commanders were unable to hold all their men and the Colonel ordered the Major to withdraw his battalion from the line. Utter confusion resulted,—there were many casualties and many were gassed. Major Norris withdrew, leaving a platoon under Lieutenant Dent on the line ignorant of the command to withdraw. They escaped finally unaided during the night.

The Chief of Staff said in his letter to Senator McKellar: “One of our majors commanding a battalion said: ‘The men are rank cowards, there is no other words for it.’”

A colored officer writes:

I was the only colored person present when this was uttered: It was on the 27th of last September in the second line trenches of Vienne Le Chateau in our attack in the Argonne and was uttered by Major B. F. Norris, commanding the 3rd Battalion. Major Norris, himself, was probably the biggest coward because he left his Battalion out in the front lines and came back to the Colonel’s dugout a nervous wreck. I was there in a bunk alongside of the wall and this major came and laid down beside me and he moaned and groaned so terribly all night that I couldn’t hardly close my eyes—he jumped and twisted worse than anything I have ever seen in my life. He was a rank coward himself and left his unit on some trifling pretext and remained back all night.

From September 26-29 the First Battalion of the 368th Infantry, under Major J. N. Merrill, was in the front-line French trenches. On the night of September 28 it prepared to advance, but after being kept standing under shell-fire for two hours it was ordered back to the trenches. A patrol was sent out to locate the Third Battalion, but being refused maps by the Colonel it was a long time on the quest and before it returned the First Battalion was ordered to advance, on the morning of September 29. By 1:00 P. M. they had advanced one mile when they were halted to find Major Merrill. Finally Major Merrill was located after two hours’ search. A French Lieutenant guided them to positions in an old German trench. The Major ordered them forward 600 yards to other deserted German trenches. Terrific shell- fire met them here, and there were many casualties. They stayed in the trench during the night of September 29 and at noon on September 30 were ordered to advance. They advanced three kilometres through the woods, through shell and machine gun fire and artillery barrage. They dug in and stayed all night under fire. On October 1 the French Artillery came up and put over a barrage. Unfortunately, it fell short and the battalion was caught between the German and French barrages and compelled hastily to withdraw.

The regiment was soon after relieved by a French unit and taken by train to the Marbache sector. Major Elser, of the Second Battalion, made no charges against his colored officers and verbally assumed responsibility for the failure of his battalion. There was a time strong talk of a court martial for him. Major Merrill made no charges; but Major Norris on account of the two breaks in the line of the Third Battalion on September 28 ordered five of his colored line officers court-martialed for cowardice and abandonment of positions— a Captain, two First Lieutenants, and a Second Lieutenant were accused. Only one case,—that of the Second Lieutenant, had been decided at this writing. He was found guilty by the court-martial, but on review of his case by General Headquarters he was acquitted and restored to his command.

Colonel Greer in the letter to Senator McKellar on December 6, writes as follows:

From there we went to the Argonne and in the offensive starting there on September 26, had one regiment in the line, attached to the 38th French Corps. They failed there in all their missions, laid down and sneaked to the rear, until they were withdrawn.

This is what Colonel Durand, the French General who was in command in this action, said in a French General Order: “L’Honneur de la prise de Binarville doit revenir au 368th R.I.U.S.”

And this is what Colonel Greer himself issued in General Order No. 38, Headquarters 92nd Division, the same day he wrote his infamous letter to this senator:

The Division Commander desires to commend in order the meritorious conduct of Private Charles E. Boykin, Company C, 926th Field Signal Battalion. On the afternoon of September 26, 1918, while the 368th Infantry was in action in the Argonne forest the Regimental Commander moved forward to establish a P.C. and came upon a number of Germans who fled to the woods which were FOUND TO BE ALIVE WITH MACHINE GUNS. The Commanding Officer ordered the woods searched to the top of the hill, the officer in charge of the scouting (2nd Lieutenant C. W. Carpenter) called for volunteers and Private Boykin, a telephone linesman, offered his services and set out with the rest of the detail. While trying to flank an enemy machine gun another opened fire killing him instantly.

This effort of the 368th Regiment was seized upon by Army gossip and widely heralded as a “failure” of Negro troops, and particularly of Negro officers. Yet the same sort of troops and many Negro officers in the Champagne and afterward in the Argonne under French leadership covered themselves with glory. The real failure in the initial Argonne drive was in American field strategy which was totally unequal to German methods and had to learn by bitter experience. It is worse than unfair to write off the first experience to the discredit of Negro troops and company officers who did all that was humanly possible under the circumstances.

Other Units

The 365th, 366th and 367th Regiments did not enter the battle-line at all in the Argonne. The whole division after the withdrawal of the 368th Regiment was, beginning with September 29, transferred to the Metz sector, preparatory to the great drive on that fortress which was begun, rather needlessly, as the civilian would judge, on the day before the signing of the Armistice, November 10.

According to plan, the 56th white American Division was on the left, the 92nd Division was in the center and the French Army was on the right. The 367th Regiment led the advance and forged ahead of the flanking units, the entire First Battalion being awarded the Croix de Guerre;—but this time wise field direction held them back, and for the first time they were supported by their own Negro Field Artillery. Beside the four Infantry Regiments the 92nd Division had the usual other units.

The 325th Field Signal Battalion, attached to Division Headquarters, was composed of four companies organized at Camp Sherman. It had then colored and twenty white officers. It was in France at Bourbonne-les-Bains and then went to the Vosges, where it was split into detachments and attached to regiments under the Chief Signal Officer. While at school at Gondrecourt, July 13–August 18, it made one of the best records of any unit. Many of its men were cited for bravery.

The 167th Field Artillery Brigade consisted of two regiments of Light Artillery (755) trained at Camp Dix (the 349th and 350th) and one regiment of Heavy Artillery (the 351st) trained at Camp Meade, which used 155 howitzers. They experienced extraordinary difficulties in training. There can be no doubt but that deliberate effort was made to send up for examination in artillery not the best, but the poorest equipped candidates. Difficulty was encountered in getting colored men with the requisite technical training transferred to the artillery service. If the Commanding Officer in this case had been as prejudiced as in the case of the engineer and other units, there would have been no Negro Artillery. But Colonel Moore, although a Southerner, insisted on being fair to his men. The brigade landed in Brest June 26 and was trained at Montmorillon (Vienne). They were favorites in the town and were received into the social life on terms of perfect equality. There were five colored company officers and eight medical officers. The officers were sent to school at La Courtine and the Colonel in charge of this French school said that the work of the colored artillery brigade was better at the end of two weeks than that of any other American unit that had attended the school. The brigade went into battle in the Metz drive and did its work without a hitch, despite the fact that it had no transport facilities for their guns and had to handle them largely by hand.